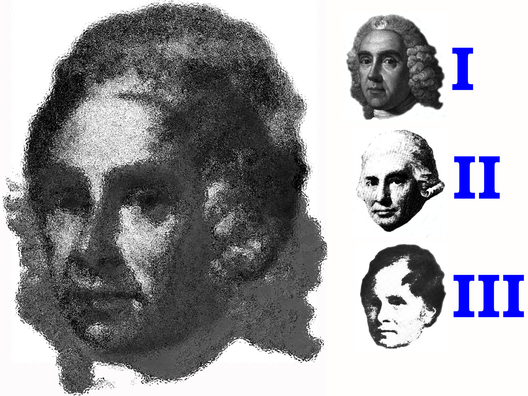

Alexander Monro I, II, III1697–1859

This is an unusual entry as it involves three generations of anatomists at Edinburgh University. They are shown in the composite image of the three Alexanders Monro: primus (1697-1767), secundus (1733-1817), and tertius (1773-1859). Alexander Monro (primus) became first Professor of Anatomy in Edinburgh, and the Monro dynasty held that chair for 126 years. In the eighteenth century many Scotch doctors (as they were then known) had obtained their training in medical schools in Scotland and many had presented their dissertations at Leyden, where Boerhaave had held court. Scotch medicine was successful, and became of increasing relevance to the emerging knowledge of the brain, because it shifted Boerhaave’s mechanistic interpretations of physiology in the direction of the nervous system. The brain and its influence on behavior became the centre of attention rather than the body and its mechanical functioning. Over the three generations of father, son and grandson they occupied the chair of anatomy at Edinburgh University for 126 years. All the Monros wrote on the brain although it cannot be said they did so with equal perspicacity. Alexander Monro (primus) studied under both Boerhaave at Leyden and William Cheselden (1688-1752) at London. His father (John Munro) was an army surgeon who had studied at Leyden and he sought to establish a medical school at Edinburgh along the lines of that at Leyden. Monro (primus) was the first professor of anatomy of the Edinburgh Medical School, founded in 1726. His Works were published by his son in 1781, and they are concerned mainly with anatomy and surgery, although there is a chapter on the nerves. Monro discussed the contemporary ideas about nerve communication (vibration or liquor) and presented evidence against both. His distrust of the notion of fluids passing along the nerves led him to carry out an experiment in which a nerve was tied: no swelling followed, as would have been expected from a circulating fluid. He did much to set Edinburgh medicine on its course as an advocate for nervous rather than mechanical involvement in animal œconomy or what we would now call physiology. He did discourse on brain injury during his lectures and noted that recovery from injury to the brain was rare. Monro (secundus) is considered to have been more distinguished than his father. He was also more disputatious. His contributions to brain anatomy were greater, and he wrote a treatise on it, as well as on the eye and on the ear. In 1758, he reported that the ventricles of the human brain all communicate with one another. This claim of discovery was highly controversial, and Monro was in public dispute with William Hunter (1718-1783) regarding it. Like his father, Monro (secundus) was sceptical about the involvement of electricity in nerve transmission. In many ways, Monro (tertius) is an enigma. He used his grandfather’s lecture notes (without changing the dates) but did contribute to work on the brain and general anatomy. He published his Morbid anatomy of the brain in 1827. Charles Darwin attended his lectures, and this is said to have been one reason why he abandoned medicine.