Samuel Johnson1709–1784

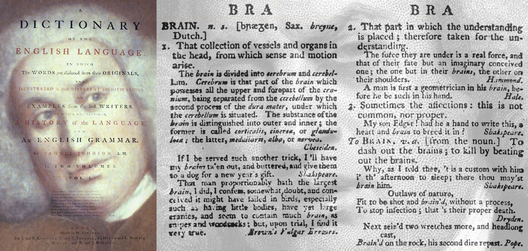

Johnson was a Doctor of Letters rather than Medicine, but he did describe some signs which are worthy of note by historians of neuroscience. It is generally stated that Johnson was short-sighted, with his left eye being weaker than his right. Indeed, his medical state has been diagnosed retrospectively by many writers. His characteristic mannerisms, ticks and gestures have led some to suggest that he suffered from Tourette’s syndrome. Johnson himself was knowledgeable about matters medical: he had written many biographies of medical men (including Hermann Boerhaave and Thomas Sydenham) mostly for the Gentleman’s Magazine, on which he worked prior to compiling his Dictionary. He assisted Robert James (1703-1776) with biographies for his compendium of pharmacology entitled the Medicinal Dictionary. He was also acquainted with some of the leading physicians in London. Accordingly, it is of little surprise that he made many statements concerning his own health as well as his vision and the problems with it. He is shown on the left in the title page of his Dictionary and on the right in his definition of ‘brain’. It is difficult to determine the details of Johnson’s eyesight from the contemporary accounts because they were so contradictory. Some said he was blind in one eye, others describe few difficulties with his vision. Johnson’s sensitivity to his own appearance is evident from the following account given (after his death) by his acquaintance, Mrs Piozzi: “When Sir Joshua Reynolds had painted his portrait looking into the slit of his pen, and holding it almost close to his eye, as was his general custom, he felt displeased, and told me, ‘he would not be known by posterity for his defects only, let Sir Joshua do his worst.’ I said, in reply, that Reynolds had no such difficulties about himself, and that he might observe the picture which hung up in the room where we were talking, represented Sir Joshua holding his ear in his hand to catch the sound. ‘He may paint himself as deaf if he chooses,’ replied Johnson; ‘but I will not be blinking Sam’”. In the same collection of anecdotes (this time from Sir Joshua Reynolds’s daughter), it is clear that Johnson was a speed reader, and there is also a hint of describing scanning eye movements: “He always read amazingly quick, glancing his eye from the top to the bottom of the page in an instant. If he made any pause, it was a compliment to the work; and, after seesawing over it a few minutes, generally repeated the passage, especially if it was poetry”. Johnson’s eyes might have been scarred by ulcers from his infancy. Boswell noted that Johnson suffered from scrofula (then called the King’s evil) as a child “which disfigured a countenance well formed, and hurt his visual nerves so much, that he did not see at all with one of his eyes, though its appearance was little different from that of the other. There is amongst his prayers, one inscribed ‘When my EYE was restored to its use,’ which ascertains that many of his friends knew he had, though I never perceived it. I supposed him to be only near-sighted; and, indeed I must observe, that in no other respect could I discern any defect in his vision; on the contrary, the force of his attention and perceptive quickness made him see and distinguish all manner of objects, whether of nature or art, with a nicety that is rarely to be found. When he and I were travelling in the Highlands of Scotland, and I pointed out to him a mountain which I observed resembled a cone, he corrected my accuracy, by shewing me, that it was indeed pointed at the top, but that one side of it was larger than the other”. Johnson never wore correcting spectacles, even though they were readily available, and he probably benefited from old age, as most myopes do, by the departure of his near point from his eyes. He continued to read without spectacles into his anecdotage! Almost all the portraits of Johnson represent him with his head tilted slightly towards the right shoulder, hence bringing the left eye closer to the midline of the head. A similar posture is assumed by those who have strabismus, in order to bring one eye closer to the midline of the body. Thus it is possible that Johnson was functionally monocular – using his left eye. This contradicts his statement about “the dog was never good for much”, but it does point to a difference in functioning between the eyes. It is the type of comment commonly made by those with a ‘lazy eye’. It remains possible that his ametropia was such that the left eye was used for near vision and the right for far. This could also account for the fact that he never wore spectacles, even in old age. Whether this resulted in him tilting his head in the opposite direction when viewing distant objects is not recorded. An alternative interpretation is that he suffered from a congenital left superior oblique palsy.